A new way of thinking

This leap into the dark coincides with a great lesson I receive from my tutor Nick Roddick.

At school we were taught to venerate our teachers and, above all, textbooks. My appreciation of, for example, Shakespeare, was learned through the prism of Shakespearean scholars like William Hazlitt, A. C. Bradley, Dover Wilson, or at the very least CliffsNotes. The teachers expected my essays to be littered with references to these experts – to prove the validity of my arguments. Their names are etched in my memory.

In my second year at university Nick gets me in for a chat and says my essays are strewn with other people’s ideas. I think I’m being accused of plagiarism, and I show him the footnotes where everything is dutifully attributed. I’m actually quite narked.

Nick’s very kind – a man of the 1960s. He’s not an actual hippy, but I think he may have dabbled. He wears a waistcoat that he might have bought in India or Afghanistan and has a slightly unkempt horseshoe moustache.

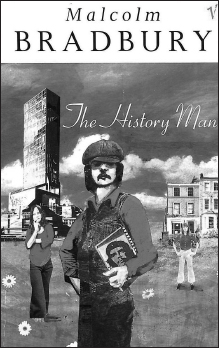

My favourite novel is The History Man by Malcom Bradbury, it’s the one I’ve reread more than any other. The main character is Howard Kirk – a permissive and radical sociology lecturer who loves stirring things up, mostly just for the fun of it.

Nick reminds me of Howard – they’re both such gentle and humorous revolutionaries. He points at my essays with their references to well-known scholars and says, with a broad grin peeking out from beneath his moustache, ‘But I don’t want to know what they think, I know what they think, I’ve read their books, I wanna know what you think.’

It’s a mental revolution.

It ‘blows my mind’, as Nick might say.

Nearly everything they taught me at school was wrong, thank God my parents weren’t paying for it.

Let that be a lesson to you!

The idea that my opinion is worth something – without a supporting argument from an acknowledged source – unblocks a dam inside my head. Up until now I’ve only been an interpreter of other people’s work, now I start to create my own. I write the department pantomime – the script and the songs (rock god); I create a one-man show and take it to the National Student Drama Festival; another group of us create a play about the Baader Meinhof group; we take new offerings to the Edinburgh Festival, new plays, two-man shows, something called a ‘review’.

But this whirlwind of creativity begins with Rik, Mike, Mark and Lloyd.

The group of five finds a name – 20th Century Coyote, a weak pun on 20th Century Fox. I’m not sure how many people get the reference, even though we play the 20th Century Fox theme tune at the start of every performance. Are we trying to suggest that we’re more wild and dangerous than the mainstream? Is a coyote more wild and dangerous than a fox? Who would win in a fight? Or is it an allusion to Wile E. Coyote in the Road Runner cartoons?

Whichever, the name sticks, perhaps because it’s so vague it doesn’t pin us down. And group names are only ever as good as the work they produce: The Beatles and The Rolling Stones are pretty poor names objectively, but carry weight because of the work associated with them.

20th Century Coyote is a happy group. Every fortnight we pile into Lloyd’s car and drive to The Band on the Wall pretending to be in a James Bond film. We sing the theme tune at the top of our voices – that tune that has the quiet bits (dum, dum, dum dum), followed by the loud horny bits – (da-da de-daah, de da-dah, daddle-de-dah, de da daaah) and Lloyd, a man who should never have been given a licence, swerves out into the traffic obligingly as we fire imaginary pistols out of the windows.

We do shows with titles like The Church Bizarre – a Fête Worse than Death and The Typig Error. In my memory they are murder mysteries? Cowboy spoofs? Is there one about a dragon? I’m sure I remember a guest performance from Paul Bradley – a fellow student who goes on to be a regular in EastEnders and Holby City – sucking deep on a fag, blowing out smoke, and pretending to be a Welsh dragon even though he’s Irish. There’s no recorded evidence to remind me of the quality of these productions, no scripts, and no photographs. So you have to rely on me to tell you what they were like.

What were they like, Ade or Adrian?

They were brilliant. God, you should have been there.

Who knows? We amuse ourselves immensely, and play mostly to fellow students from the Drama Department who come along to give us support.

I hand the hat round at the end of every performance – our only chance to make any money – and on one occasion I approach a couple of women sitting near the back who look like they’ve just popped in for half a shandy whilst waiting for a bus. One woman reaches into her purse for a couple of coins but her friend puts out a hand to stop her.

‘No, don’t,’ she says. ‘They’re only strolling players.’

Her friend puts a few pence in the hat anyway, but I barely notice because I can’t wait to tell the boys. I rush back to the toilets where they’re changing amongst the puddles of piss and johnny machines.

‘Strolling players!’ I shout. ‘A woman just said we’re strolling players!’

We are cock-a-hoop. Strolling players. This is the validation we’ve been seeking. This is tantamount to being called professional artistes. Who needs an Equity card when someone is already calling us strolling players.

Turns out we do. The proprietor of The Band on the Wall doesn’t see enough of an increase in his lunchtime trade and the dodgy Variety contracts do not materialize. We stop doing the gig after a few months.

Our last outing as a group of five is to the Edinburgh Fringe in 1977. Though Lloyd Peters has been replaced by Chris Ellis, who you might remember from The Young Ones as one of the sixteen-year-olds on ‘Nozin’ Aroun’’ complaining that he can join the army and kill people but can’t go into pubs. Mark Dewison also turns up a few times in The Young Ones as Neil’s hippy friend who dresses exactly like Neil, has long hair like Neil, and is also called Neil.

The Edinburgh experience in the seventies is very different to the glitzy one you hear about today. It’s amateurs and students. Brotherhood of Man are top of the charts with ‘Angelo’ and people are driving around in beige-coloured Austin Allegros – and that’s pretty much how it feels.

We go up as part of Manchester Umbrella. As the name suggests it’s an umbrella organization for lots of different shows, all from Manchester University. And a joke about how much it rains in Manchester. It does rain a lot. We are perpetually damp.

We hire the Zetland Hall in Leith. It looks like a large semi-detached house from the front but behind it expands into a spacious hall that is used for ceilidhs by the Shetland Society, who own the place.

Manchester Umbrella is a massive outfit – we are like a mini festival in one venue, we put on several plays, a revue, poetry readings and even a dance event, and there are perhaps forty of us in the company.

We all sleep . . . in the hall. Yes, we sleep in and amongst the scenery and the chairs, simply crawling into sleeping bags and lying on the bare wooden floor. The night-time lullaby is the sound of people trying to have sex without making a noise. One girl picks up the wrong glass of water and drinks someone else’s contact lenses. Could have been worse.

Every morning we have to get up early and start queuing for one of the two bathrooms, because the doors open at 9.00 and the first show starts at 10.00. Many of us never make it to the front of the queue. I imagine the hall stinks of unwashed students and leftover spud-u-like (not a euphemism), which is probably one of the reasons our shows are so ill-attended. That and the fact that we’re so far away from the main drag in Edinburgh.

There’s a company rule that we won’t go through with a performance if the cast outnumber the audience but we have to forgo the rule pretty sharpish or we’ll end up doing no shows at all. Apart from the japes and the constant boozing it’s a pretty dispiriting experience.

Our show in 1977 is called My Lungs Don’t Work – I can’t recall anything about it, and wonder if there isn’t much to remember. Ever since we stopped the shows at The Band on the Wall the group has fallen into some kind of limbo.

It feels like the world changes in the summer of 1977. It’s when Elvis Presley, Groucho Marx and Grandma Ed all die; when Ron Greenwood becomes the England manager, when the National Front are rebuffed at the Battle of Lewisham, when Virginia Wade wins Wimbledon, and when The Sex Pistols get to number six with ‘Pretty Vacant’. I don’t know which, if any, of these is a possible catalyst, but the time is ripe for change, and when we return to Manchester 20th Century Coyote is just a two-man outfit – Rik and me.